Iryna Loskot

Multidisciplinary artist

Iryna Loskot

(2001, Mirny, Yakutia/ moved to Kharkiv, Ukraine, in early childhood) is a Ukrainian multidisciplinary artist. Her practice explores the exploitation of the environment and resistance to this exploitation. In her work, Iryna explores the political connections between humans and non-humans. Her approach involves revealing the agency of non-humans, the militarization of nature, and the naturalization of warfare. The artist seeks to undermine the anthropocentric view through images of blurring boundaries between human and non-human experiences.

Shared flower garden

participatory project, object, 2025

The work was implemented as part of the Jam Factory Art Center's art and community project “The Land We Carry,” which is part of the Magiс Carpets residency program, co-funded by the European Union's Creative Europe program.

The flower garden was planted together with the participants, most of whom have experienced forced displacement. The plants include both wild and cultivated species, with which the gardening participants have personal memories and stories. Wild plants — those that grow without human control — are often ignored or considered undesirable in well-kept gardens, where people strive to get rid of everything “unknown.” According to the artist, who herself has experienced displacement, this flower garden echoes the experience of marginalization of displaced persons in Ukrainian society.

Memories should be heard, so the communal flower garden is designed as a place to meet friends, where people can spend time together, and as a space to encounter the stories of others:

The audio, which is accessible via a QR code, combines excerpts from the participants' memories and the sounds of musical instruments, reminiscent of an attempt to recreate a familiar but elusive melody. The scents of plants work in a similar way: they can transport us back to the past. A multimodal experience can help us remember our own stories and find a place for them in the communal flower garden.

Nothing grows here

solo show, 2025

Materials: boots, soil, apples, acrylic plastic sheets, water, dried tomato skins, hand cream, audio

In 2025, in the village of Ivanivka in the Sumy region (Ukraine), my grandmother passed away. At that time, I was in Kyiv (Ukraine). Unable to find a way or the financial means to come on the day of the funeral, I arrive a day late. I am no longer traveling to a funeral, but to a garden with the things she left behind.

All forms of care eventually come down to the gesture of walking: leaving, returning, fermenting/meandering.

As I tend to the garden, I think about tending to a sick body. In both processes, daily return and repetition matter. Reflecting on lateness as one of the temporalities of wartime, I weave together sound recordings from the

garden and my work within it: last year’s with this year’s, trying to grasp a new understanding of time.

My grandmother’s illness stood in opposition to the rhythms of air-raid alerts and news, and thus fell out of visible time. Drawing on Sandilands’ ideas, I think of illness as a process in which a body becomes a landscape of catastrophe, yet no one sees this catastrophe because it unfolds on a different scale.

Observing the scale of my loved ones’ pain, I become increasingly aware of death as a prolonged process of disorientation in the space of both the living and the non-living. During decomposition, the first to emerge from the body are gases and fluids. The molecules of these fluids split and bind at once, and if a person, as a meaning within the world of signs, is constantly being

reassembled through relationships, then I look at the choreography of the liquid molecules as a possibility for reconfiguring human–nonhuman relations into an entirely different (non)form. When these fluids seep into the soil, a shared fermentation begins. When I think about the future, I think about gardens without humans and without fluids. This exhibition invites you into its fermentation.

UnderEocened

found object, 2025

Materials: stone, amber, pine resin

The exhibit documents the physical and chemical transformation of the mineral, triggered by catastrophes of such magnitude that amber is restored to its original state of resin, in the opposite direction of geological time, to the Eocene, when mineralization had not yet occurred. Catastrophes restart geological processes, cancel established phases, and roll back matter to the pre-Anthropocene era, offering humanity a new state of liquid and formlessness to become conscious participants in slow geological change.

Invitation

sculptures, іnstallations, 2024

Materials: glass flask, compost, plastelin

The earth's digestion of itself is both a self-destructive and self-healing process. During warfare, it shows this ability more vividly. Adapting to reality, the land offers to enter into an interdependent symbiosis to be digested and transformed into everything or nothing. “We require each other in unexpected collaborations and combinations, in hot compost piles. We become-with each other or not at all”(Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Donna Haraway, 2016). The artist captures the earth with the help of glass shapes to express an invitation to symbiosis.

Military

art object, 2024

Materials: glass aquarium, stones, Riccia floating plants, fabric, silicone gel

The environment begins to mutate, adapting to the war, which is taking deeper root in its structures. Natural processes are disintegrating, giving way to new, hybrid life forms that are forced to invent new survival strategies and growth algorithms that go against established ecological processes. The mutation of the military uniform and the algae makes it difficult to understand who is camouflaging whom: the human or the non-human.

Wakeful lion

video, 2024

The video work explores and fantasizes about the invisible effects of war on the bodies of humans and non-humans, emphasizing the similarity of external and internal reactions of bodies and at the same time the inaccessibility of fully understanding each other's experiences.

*photo by Peter Michal/sopa gallery

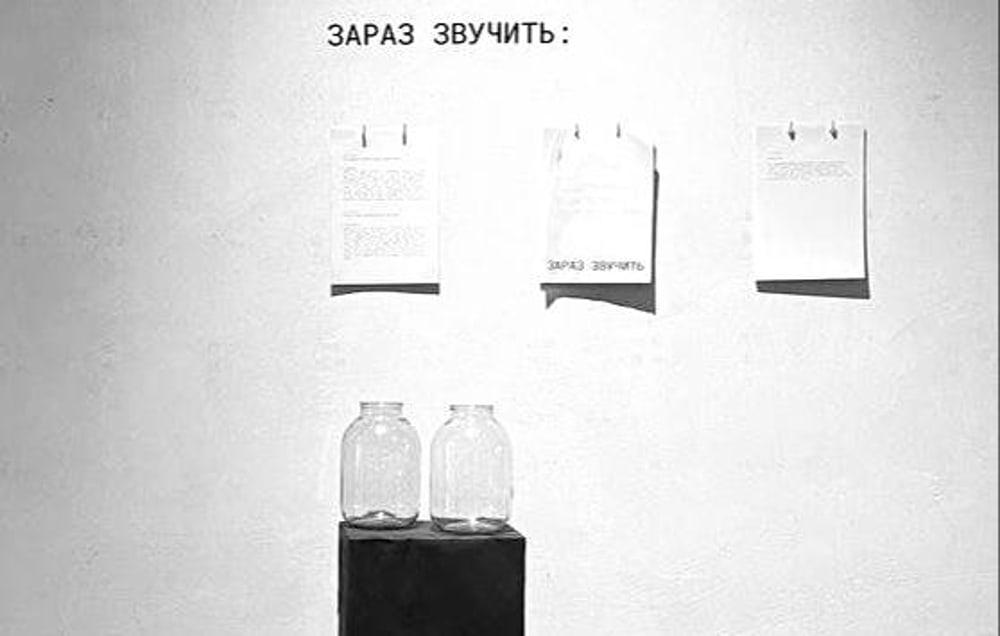

On the future

audio installation, 2024

Taking care of your loved ones in a household often involves caring for the land and plants.

In this broadcast, you can hear the sounds coming from a garden where people are working. This is happening in the village of Ivanivka, Sumy region, which is 36 kilometers from the border with Russia. Every summer, my mother works in the garden to prepare twists of vegetables and jam for the winter, some of which she gives to me.

In the threatening future, due to Russian aggression, if the canning jars are not filled, it puts the entire chain of care at risk. Will they be filled with tomatoes? Will the landscapes I broadcast remain intact?

*dim zvuku

Camouflage

art‒object, 2024

Materials: wood, fabric

A piece of camouflage fabric appears on the bark found in the forest in Sumy region. Obviously, the process of adapting the environment to human warfare has begun. This mutation makes it difficult to understand: is it human or non-human that is camouflaged?

*1 ‒ photo by Jurgen Huiskes/Yermilov Center

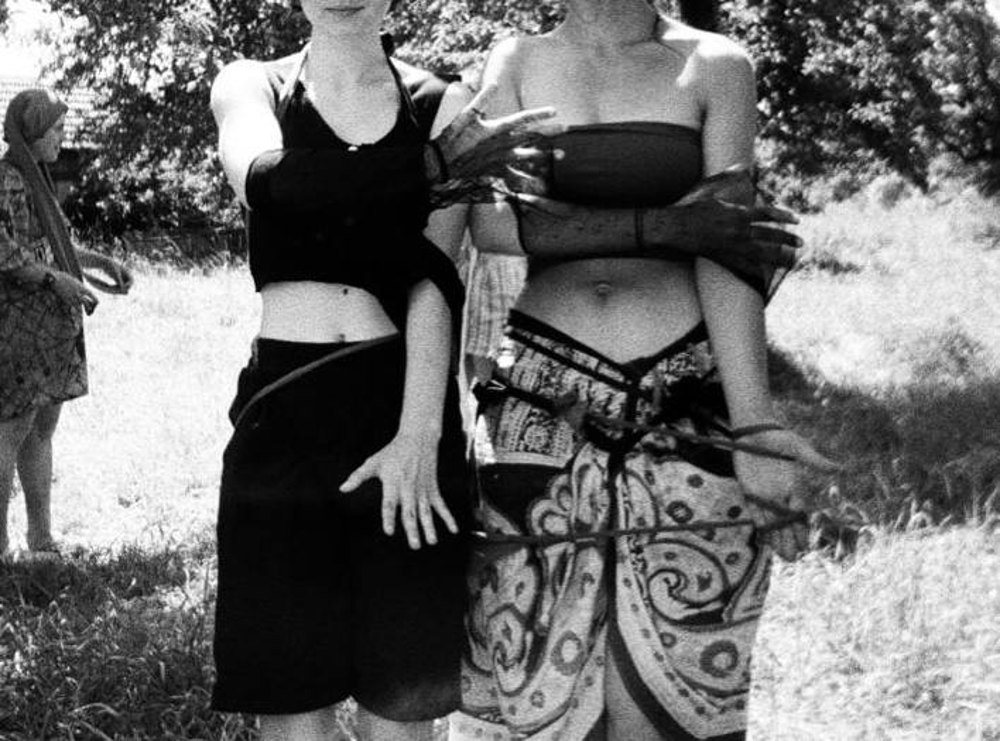

Migrant from the Garden

participatory project, video, 2024

In honor of my birth, my grandfather planted a plum tree in the village of Berezivka, Sumy region. This village was occupied by Russia in 2022 and later de-occupied. Now, because of the danger associated with the proximity to the Russian border, people in Berezivka have stopped caring for the garden and my plum tree is only watered by rain. I am relocating the plum tree to a safer area, even though it will have to start life "from scratch." I suggest that migrants take care of the relocated tree so that they do not forget to take care of each other.

The tree was planted in the city of Przemysl (Poland), in the garden where there is a shelter for Ukrainian refugees. In the video, the artist and the displaced people who volunteered to help with the gardening plant a tree. Serhiy from Nova Kakhovka sincerely promises to take care of the plum tree.

*photo by Olga Filonchuk

Defocusing

ready‒made, 2024

Man, animal, and earth merge with each other at the time of death. During life, man identifies himself by contrasting himself with the animal.

The squares, which are the figurative equivalent of human and non-human, are blurred and look fuzzy on this side of the board. This opens the way to blurring the boundaries between the memory of humans and the memory of non-humans and undermines the hierarchy between them.

The work is part of the personal exhibition "In Memory of People and Animals" and is presented at the National House in Przemysl (2024)

*photo by Olga Filonchuk

Memorial

appropriated object, 2024

Material: wood

Usually, the resources of horses are used for transportation, food, clothing, and as a component of film photographs, etc. I am trying to suggest that we abandon the objectifying view of animals and look at the chess piece as a monument made in honor of animals.

The work is part of the personal exhibition "In Memory of People and Animals" and is presented at the National House in Przemysl (2024)

*photo by Olga Filonchuk

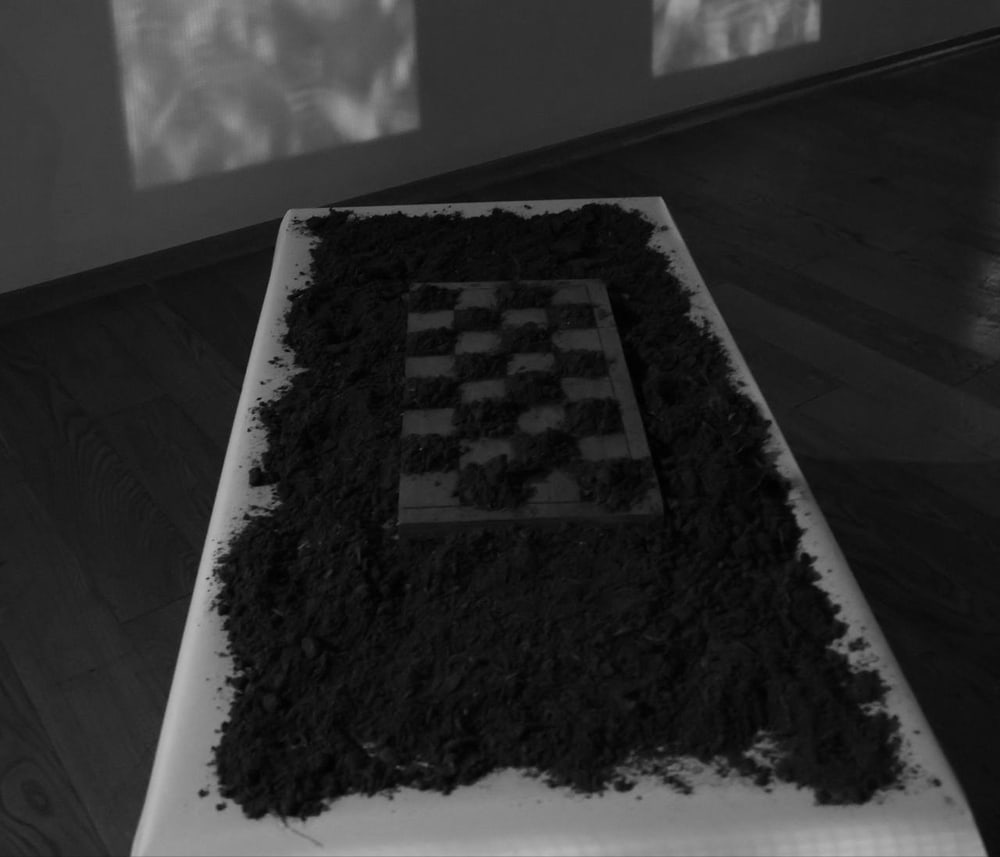

Battlefield

installation, 2024

Materials: chessboard, earth

A chessboard is a battlefield for a chess match. The pattern formed by the ground on the board resembles the battlefields on the territory of Ukraine, which are disfigured by sinkholes. The land becomes not only a background, a battlefield, but also a participant in the battle itself: a defense, an enemy, and an object of struggle.

The absence of land in some parts of the board means gaps in the ecosystem due to constant Russian shelling.

The work is part of the personal exhibition "In Memory of People and Animals" and is presented at the National House in Przemysl (2024)

*photo by Olha Filonchuk

In memory of

people and animals

installation, photo, 2024

Materials: photo, candle

This old photo was probably taken in memory of the people in it. The horse/calf in this film photo lived with our neighbors in the village and most likely appeared in the picture by accident.

Film photographs are made from the skin of pigs and cows, fish scales, bones of cattle and ungulates: buffaloes, bulls, yaks, and horses. The representatives of the animal species in the photo may be part of the film on which it was taken.

This candle burns in memory of animals that have suffered from human whims.

The work is part of the personal exhibition "In Memory of People and Animals" and is presented at the National House in Przemysl (2024)

*photo by Olha Filonchuk

In front of the ruins

photo documentation of land art, 2024

The work was created in collaboration with 6th grade pupils of Lyceum No.51 in Lviv, Ukraine.

The future generation creates monuments dedicated to the events of the past. The monuments are created according to the principle that they change over time. The decay of material things coincides with the process of forgetting, which is inherent in time.

Thus, I am thinking about the fluidity of memory. How will the next generations remember today's events after a certain period of time? Will they forget about the material destruction caused by the Russian Federation? Or, on the contrary, will the experience of creating temporary monuments remind them of the current events in which Russia is trying to destroy memory?

The work was created within the framework of the program "Artists After School" Curators: Olga Krykun, Masha Kovtun, Romana Bartunkova.

The Garden

cartoon, 2024

The cartoon is based on the author's real memories. These memories are related to her childhood in the village of Berezivka, Sumy region. In her recollections, the artist recognizes her inability to control the course of events. In this way, the work interacts with Timothy Morton's idea of "dark ecology," in which he calls for recognizing that it is not always in our power to influence phenomena. The work non-verbally asks the following questions: what does it feel like to live in a world that does not belong to us? What does it mean to recognize that something may not belong to us?

At the end of the cartoon, real photos of the place where the story takes place are added.

Composer: Clemens Pool

The work was funded by Artist at Risk

Longing for the plum

video, 2023

In honor of my birth, my grandfather planted a plum tree in the village of Berezivka, Sumy region. The village was occupied in the first months of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine and later de-occupied. For some time, I could not return to the village because of the threat from Russia and could only imagine that place and the life of my plum tree. I wondered how the invasion had affected the tree: whether it was alive, whether it had enough water, whether the taste of its fruit had changed...

Worried about my plum tree and homesickness, I sang a wistful Ukrainian folk song called "Tuga za tugou".

Curators: Diana Derii, Kris Voitkiv

Bluebeard

performative documentary play, 2023

Ivano‒Frankivsk (Ukraine)

The performance refers to on Charles Perrault's fairy tale "Bluebeard". In this story 8 women were trapped in the secret room. The aim of this work is to tell 8 stories of women from different cities of Ukraine who explore the collective memory of their families. In particular, particularly such events as the Holodomor and two world wars.

Рroducer: Memory Lab Ukraine

Theatre Director: Sonya Slyusarenko

*photo by Sergiy Paliychuk

Birdsong

video, 2023

Birdsong is usually used to convey the harmony of "nature".

The subtitles illustrate the "peaceful" sounds of "nature" presented in the video and the sound that are unlikely to be heard because of the discomfort they cause.

In this way, the delusion nature of the peaceful soundscape is exposed, as well as the invisibility of the problems of exploitation and violence.

The work was created as a part of the "Navigation" project at Jam Factory Art Center (2023)

Curator: Olena Kasperovych

Victory

video, 2023

The video is based on the Soviet TV film "Your Breath, Earth..." (1986). The film praises the work of Ivan Kisenko, the head of one of the most productive kolkhozes in Soviet Ukraine named “Victory". Describing his success, Ivan (a veteran of WWII) compares nature to the enemy and the agriculture work to the battle in the war.

Ivan Kisenko metaphorically compares his action to the chess game: "Nature moves 'white' and the man responds to its moves". So in the second part of the video, I covered the footage with the black squares that remind chessboard and deprive viewers of the opportunity to see the whole picture. In this way, I visualized that the idea of interacting with nature as an enemy in war justifies exploitation as a phenomenon and also underlies the policy of imperialist warfare, which consequently deprives us of life on Earth.

The work was created as a part of the "Navigation" project at Jam Factory Art Center іn cooperation with the Lviv City Media Archive

Curator: Olena Kasperovych

*photo from the gallery by Zlatoslava Kryshtafovych

Musical

The Musical Collective

film, 2022

Lviv (Ukraine)

The musical is presented in the form of a series of video posters documenting the collective process that lasted for a month. Each poster is cut by a different participant/group of participants, offering a new perspective on the documented events of the music residency. This is a continuation of the original approach, as the absence of a clear script encouraged joint activities even in the absence of a common vision - which in turn supported the practices of self-organization and shared responsibility in this newly formed wartime community.

The residency was held within the framework of the Kindling project from the Baltic Art Center, together with Milvus Artistic Research Center, soma.majsternia, Sorry No Rooms, with the support of the Swedish Institute.

Curator: Olha Marusyn

*photo by Wolfgang Obermair/hoast

Ukraine

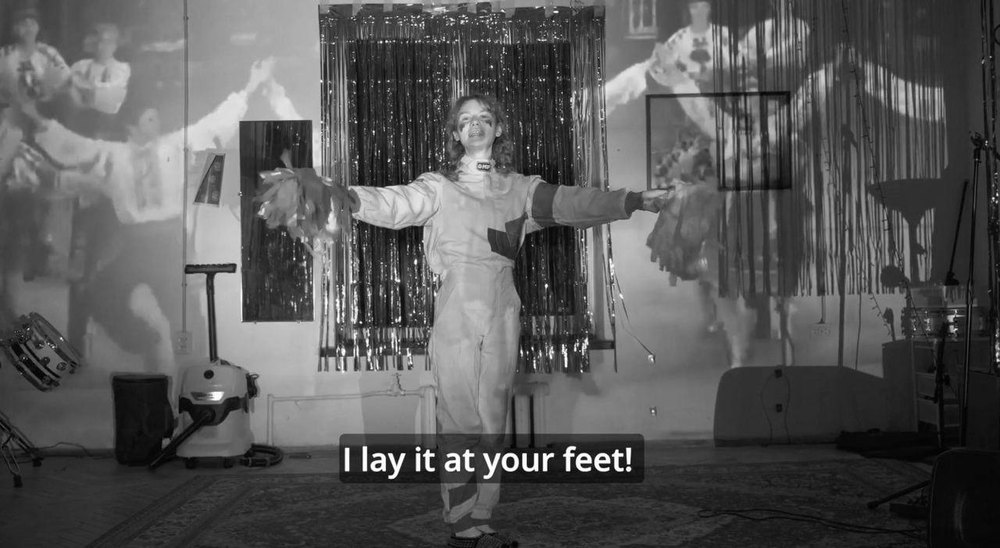

reenactment, 2022

Lviv (Ukraine)

*The song "Ukraine" by Taras Petrynenko was performed on stage during a party as part of the Musical residency in Lviv in 2022, curated by Olha Marusyn. The residency took place with the participation of IDPs and volunteers from the independent organisation Soma.majsternia, where they lived their shared experience of the war as a newly formed collective.

The work ironically reflects on the question of love for the homeland and refers to the artist's personal experience of being forced to perform Ukrainian patriotic songs at school events while studying at college. The reenactment of the school performance is an attempt to re-appropriate this traumatic experience and free oneself from an objectifying view of oneself. The props, such as yellow and blue pom-poms made from garbage bags, and the overall choreography are recreated from real memories. The projection on the background is a real performance where the artist participated in 2016.

*photo by Vitalii Garan /91 gallery and Wolfgang Obermair/hoast

Ukraine in Europe

performance, 2023

Oronsko (Poland)

The author performs the song "Ukraine" by Taras Petrynenko, which she was forced to sing at school events in 2016. The choreography and props are based on the artist's real memories. Behind her, a real performance of the band she was a part of is broadcast in honour of the Defender of Ukraine Day.

At the beginning of the song, the performer reads a text about how she was forced to sing this song when she was 15 years old, and now she is forced to sing it in a European city because of Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

*photo by Ewa Szatybelko/Museum of Contemporary Sculpture

Nuclear war

performance, 2022

Lviv (Ukraine)

The performer throws walnut kernels on the ground in the urban space of Lviv and calls this process "nuclear war". The artist creates the myth of the "walnut kernel war", which echoes Russia's claims of using nuclear weapons. In this way, she demonstrates the artificiality of both myths. In addition, by playing with language, she neutralises the pressure of anxiety caused by Russian psychological operations.

The work was created with the help of the scholarship programme COUNTERMYTH (Totem Centre for Cultural Development) with the support of House of Europe.

*photo by Maksym Shevchenko

CV

- Education

2018 - 2019

- Kyiv National I. K. Karpenko-Kary Theatre, Cinema and Television University, BA - puppet theatre actress

2019 - 2023

- Kharkiv National Kotlyarevsky University of Arts, BA - puppet theatre actress

- Selected residencies

2022

- Soma.majsternia, Lviv (UA)

2023

- Memorylab, Ivano‒Frankivsk (UA)

2024

- (AR) at Assortment Room, Ivano‒Frankivsk (UA)

- “Decentric Circles” Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw and WORK HARD PLAY HARD working group, Warsaw (PL)

‒ KAIR, Kosice (SK)

- AіR іn Liepaja, Liepaja (LV)

2025

- Scattered Communities program. Curators: Yaroslav Futymsky, Serhiy Klymko, Alyona Karavay, (online)

- "The land we carry" Jam Factory Art Center, Lviv (UA)

- "Forest Assembly of Educational Fiction" WORK HARD PLAY HARD working group, Massia (EE)

- Publications

2023

- Anna Soucek. "Kunstprojekt "Soma". Ö1Mittagsjournal

- Jakub Gawkowski. “This Show Is Not About the War: Ukrainian Artists in Poland and the Burden of Representation”. E-flux

- Musical. Concert vitan’ . Block Magazine

2024

- Yelyzaveta Karpiuk. "An exhibition by the Memory Lab collective opened in Kharkiv. It explores the themes of memory and corporeality". DTF/magazine

- Catalog “Ukraine on Fire” Laboratory of Contemporary Art “Small Gallery of Mystetskyi Arsenal”

- Kostiantyn Doroshenko. "To the City and the World. Geography of Solidarity in Kharkiv Art Center". Radio Svoboda

2025

- Oleksii Minko "Lord, help me to survive in the midst of this deadly love: Iryna Loskot's exhibition and the ecology of the artistic environment". Artslooker

- Yana Kachkovska “Everything has its own politics”: artist Ira Loskot about the exhibition “Museum of Unimpressive Mutations”. Suspilne Culture

- Workshops

- lend‒art workshops at Femmaysternia, Lviv (UA) 2024

- "Touch some grass" WORK HARD PLAY HARD working group, Warsaw (PL) 2024

- "Transplant" Šopa Gallery, Kosice (SK) 2024

- participatory project, Liepaja (LV) 2024

- Community Kitchen “Circle of Care: Earth‒Human”, DCCC, Dnipro (UA) 2024

- the project "Artists after school", Lubyanka (UA) 2025

- the project "The land we carry", Jam Factory Art Center, Lviv (UA) 2025

- the project "Artists after school", Bucha (UA) 2026

- Solo exhibitions

2024

- pop‒up "In memory of people and animals" Ukrainian National House, Przemysl (PL)

- pop‒up "Wakeful lion" Šopa Gallery, Kosice (SK). Curators: Petra Houskova, Monika Padejova

2025

- "The Museum of Unimpressive Mutations" Mala Gallery of Mystetskiy Arsenal, Kyiv, (UA)

‒ "Nothing grows here" The House of Sound, Lviv (UA)

- Selected group exhibitions

2022

- "Only Achilles" L'Atlas, Paris (FR) (as part of The Musical Collective)

- Kyiv Dispatch, Ukho Music and InterAKT Initiative, Stuttgart (DE) (as part of The Musical Collective)

2023

- "Greifbar" Saarlandmuseum Modern Gallery, Saarbrucken (DE). Curator: Iryna Yeroshko

- "Countermyth" Totem Cultural Development Centre with the support of House of Europe, (UA) Curator: Olena Afanasieva

‒ Performance Platform Lublin 2023 festival at Labirynt Gallery, Lublin (PL). Curator: Paulina Kempisty

‒ Baltic Art Center Gotlands konstmuseum, Visby (SE) (as part of The Musical Collective)

‒ "How are you?" Ukrainian house, Kyiv (UA) (as part of The Musical Collective)

‒"Concert vitan'" Hoast Gallery, Vienna (AT). Curator: Ekateryna Shapiro‒Obermair (as part of The Musical Collective)

- Kyiv Biennale “Against the Logics of War“, Assortment Room, Ivano‒Frankivsk (UА) Curators: Alona Karavaі, Yarema Malashchuk, Anton Usanov, Roman Khimey. (as part of The Musical Collective)

‒ Irish Biennial 2023, EVA International Biennale, Limerick (IRL). Curator: Sebastian Cichocki (as part of The Musical Collective)

‒ 10th Young Triennale: "Consolidation", Museum of Contemporary Sculpture, Oronsko (PL). Curators: Lia Dostlieva, Andriy Dostliev, Stanislav Mlatsky

‒ "Navigation 2023" Jam Factory Art Center, Lviv (UA).

Curator: Olena Kasperovych

2024

- Assortment Room, Ivano‒Frankivsk (UA). Curator: Alona Karavai

- "Women of Lot" Some Рeople, Kharkiv (UA). Curators: Anna Potiomkina, Diana Derii, Kris Voitkiv

- "Hostynets. The offering" 91 Gallery, Frankfurt (DE). Curators: Tamara Turliun, Anton Usanov, Olga Stein (as part of The Musical Collective)

‒ "As of now, it is quiet" The House of Sound, Lviv (UA).

Curators: Natalia Revko, Valeria Nasedkina, Andriy Linik

- "Artists after school" The Palace of Arts, Lviv (UA), National Gallery Praha (CZ). Curators: Olga Krykun, Masha Kovtun, Romana Bartunkova.

‒ "Sense of safety" Yermilov Center, Kharkiv (UА).

- "Playgrounds" International festival of contemporary animation and media art LINOLEUM, Kyiv (UA)

- "Who else holds that field dear?" DCCC (&Hospitalfield), Dnipro (UA). Curators: Diana Khalilova, Kateryna Rusetska, Lora Manofild, Siseli Farrer

- "Sensory imagination" LMMDV, Liepaja (LV). Curator: Maija Demitere

2025

- "The land we carry" Jam Factory Art Center, Lviv (UA) Curator: Olena Kasperovych

2026

Pinchuk Art Center, Kyiv (UA) Curators: Oleksandra Pohrebnyak

- Awards

- Collection

Yermilov Center, Kharkiv (UA)